Dan Morris Interviews Adeena Karasick on CHECKING IN

DM: Adeena: The title poem of your new book covers around the first half of the volume and weighs in at over thirty pages of text. “Checking In” is a playful phrase of many meanings.

I think of the term's use in 12-step recovery programs. You allude to the connection between Checking In and recovery programs in the line:" Schoenberg is starting a 12-Step Program." (p. 18). The reference to 12-Step programs and Schoenberg alludes to his development of a revolutionary music composition technique. Anthony Tommasini describes “twelve tone” music in The New York Times (2007): "Schoenberg’s use of systematized sets of all 12 pitches of the chromatic scale — all the keys on the piano from, say, A to G sharp — was a radical departure from tonality, the familiar musical language of major and minor keys."

So, the slippery texture of the title, Checking In, has taken me to Schoenberg. I now want to ask you about the relation between Schoenberg's "departure from tonality, the familiar musical language of major and minor keys" and your poetics in Checking In. With your whimsical, punning, and allusive method, you most certainly do depart from a literary language that distinguishes between "major" and "minor" referents. By that I mean Where's Waldo, Abba, the musical Annie, Dr. Dootlittle, and Carly Rae Jepsen's "Call Me Maybe" take pride of place alongside "Highbrow" literary, theoretical, musical and avant-garde references to heavy hitters from Bakhtin, Baudrillard, Benjamin, and Brecht to Mrs. Dalloway, Maria Damon, and Moby Dick.

But, to return to my inquiry about the title Checking In. So many other resonances besides Schoenbergian 12-stepping. To check in is to announce one's arrival...to die…to communicate about one's status (as in, I'm checking in on the status of that manuscript your press has been sitting on for three years), simply talking, recording something, returning something (such as checking in a book back to the library), and, of course, signing oneself in for treatment (I'm checking myself in to rehab...).

But the question I want to ask you is about the meaning of Checking In in terms of checking in to read one's email or social media. The graphic design for the long poem "Checking In" resembles a digital-social mediation: Twitter or Facebook. On the bottom of each page one finds icons -- "like," "comment," and "share" – representing how users interacting/responding to Facebook/Twitter communications. And yet your book is decidedly NOT a digitalized experiment in new media poetics where users can directly respond to your missives. “Checking In” is not a hypertextual electropoetic digital audio project I associate with folks like Chris Funkhouser -- whom you acknowledge in your book. Your book is most definitely a book. It is intertextual, polyreferential, semiotica in flavor for sure, but it reads like a book. (I think of the Campbell's hearty soup ads of yore in which the manly canned stew 'eats like a meal,' but we should use a spoon so as not to miss a drop.) It is a beautiful thing, your book. A lovingly crafted small indy press poetry object. I am interested in such in-between poetic projects. I've written, for instance, on Noah Eli Gordon's inbox, an independent press poetry book composed of actual emails that appeared in Gordon’s inbox concerning the alt-poetry community.

Adeena, you and I are of a certain age (mid 50s). Guys like us were not born digital. (I started my dissertation in the late 80s on a typewriter, and switched to a first generation boxy Apple around chapter two of my project on WC Williams). And so I am interested in between-er projects such as Checking In in terms of its relationships to the tradition of alternative press small run poetry books AND to the Born Digital electropoetics to which your text alludes and imitates in its semiotic layerings and comfort with plays on major/minor disruptions: HD meets Dr. Doolittle and the like.

Please, then, reflect on the status of Checking In as a book? Issues of audience reception come to mind. I was very comfortable with your range of references because I am in your circle in terms of years on the planet and attractions to Jewishness, music, avant-gardism, and theory. I am proud to have published a story in my undergraduate literary magazine that referenced Pere Ubu (the band and the play). I, too, think Maria Damon's "fabric exposes the poetics of everything." And so I am a target audience. I like. But, as for the question, do you think much about distribution, audience, communities of interpretation? Would you think about those questions differently if "Checking In" was not published as a book? What if “Checking In” existed exclusively online, in a format where folks could actually respond with "like," "share," "comment"?

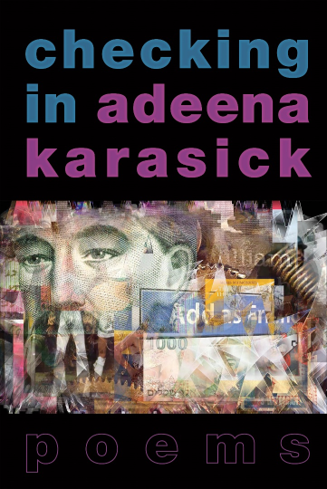

AK: Ah Daniel, you offer so many interesting “probes” here and i have to say it’s so refreshing and heartwarming to have such a close and thoughtful reader to respond to. So yes, Checking In navigates between a mediatic territory of both book (sculptural text object) yet is firmly entrenched in the world of digital media as the title poem’s very premise is grounded in Facebook updates. As both author of now 10 books and creator of media art / videopoems / pechakuchae, i inhabit both of these worlds -- and though i love, with the advent of new media and digipoeisis the new possibilities available for language, my heart is (as has always been) firmly rooted in the notion of the book – physical, material and viscerally accessible. Dedicated to that, i recently designed the newly established “Book Minor” at Pratt, where students can literally study all things book – historically, aesthetically, philosophically, exegetically.

So yes, Checking In for me as art object, is both a repository and a meaning generator marked by production, consumption and (non)utility. Each page a sculptural space of ever signifying variables; aromatic, tactilic, and sensorially alive. And to this end, i am so grateful to my indy press, Talonbooks (who has stood by me for 25 years and giving in to my “spark joy” maximalistic aesthetic; generously allowing me the freedom of design, of covers, of interiors with full color genre blurring collage essays, “excessive” typographical, concrete / vispoetic play – none of which are available as e-books,

inviting the reader to play this book as music, turning its pages, caressing its text, hearing it.

And so i adore how you mention the Schoenberg line – because in fact there are so many zones of intersection with his thinking. Most notably perhaps, in the way that Checking In moves between major and minor referents in the jouissey mash-up of pop culture and Kabbalistic hermeneutics, media theory and midrash, contemporary poetry, philosophy, semiotics, movies and pop songs; all commenting on each other asking us to re-hear or see them from different vantage points. And this ironic / paradoxical juxtapositional play of otherness is kinda Schoenbergian -- the way his dodecaphony ensures all 12 notes of the chromatic scale are sounded as often as one another – while not fetishizing any one note. Similarly, all multigeneric and “all–access” with Checking In there’s a kind of de-hierarchizing of information, a levelling out (where say “King Ubu is dining at Nobu, Gargantua and Pantagruel are listening to They Might Be Giants, Immanuel Kant liking No Doubt, and Uber Allis is driving for Lyft). Taking the reader on a satiric tour through the shards and fragments of literary and post-consumerist culture, to put it in Schoenbergian terms, it too, avoids being in a specific key. Not just the title poem, but in fact the whole book moves through a wide variety of tones, microtones, feels, foci – whether that be homophonic translations, (Pound, Olson, Wittgenstein, Cicero); the infusions of vispo, a re-setting of bp Nichol’s “blues”, “Score for Diacritics”, (a satirical mashup of the markers of pronunciation); the repurposing of Lorum Ipsum (Cicero’s, 45 BC treatise on the theory of ethics re-translated as a passionate love poem. Full of transpositions, and inversions, it’s continually “checking in” with itself -- itself which is always something other.

And in the spirit of “otherness”, i love how for you, the title reminds you of checking in to a clinic. In that sense, the book would offer a zone of recovery ha! i was thinking more in term of dis-covery, ie how “Checking In” not only refers to the act of reporting, enrolling, registering or recording one’s arrival or status, but also hidden in its homonymy, “checking in” as “shakin’”, ripping one from their normative reading habits. Chacque’n in, intralinguistically highlighting how the “same” is always different, how (in the words of Derrida), “every other is every bit other”. Or “checking” as in “checked” as a multicolored, harlequinesque cubist motif, patterns of repeating elements; or “checkered” in the sense of a past of varied fortune, credible and incredible incidents ever re-presenting themselves. Or “checking” as in an account, an accounting; an economy of exchange. So all checking and re-checking, shickered up, “shooketh” ‘n shirkin responsibility, or in a Beyoncé-esque sense of “Check It Out”, “Checking In”, also references the sense of checking as examining something, scanning, surveying, scrutinizing it in order to determine its condition, detect the presence of something; asks the reader to stop or slow down, as one peruses, probes, analyses, inquires.

So yes, “Checking In” does become so much more than just the beckoning of the Facebook platform. For me, there is one other reference that i am continually haunted by, and kinda underscores everything -- If according to Kabbalistic hermeneutics the world was created through letters, their very expansion and contraction (mirroring the very act of meaning production), then in some ways the world can be seen as some giant 3-D pop up artist book that we live in and recreate with every “reading”. And in a kind of Jabèsian way, we enter its warm flesh; enter it sometimes through the skin of its meaning, its form. Enter it with vigilance through its thresholds, agonies and garrulousness, through its illegibilities and dissimulation, disguises, dreams, affirmations and displacement between the writing and the written and the yet to be written where all is shattered fragmented; wandering and rebellious between borders, orders, laws, flaws, codes, idioms, territories, terrortories, deserts and promises, questions, probes, anxieties, abandonments absences abscesses, obsessions and flourishes. And literally BOOK ONESELF IN, enter it as a dwelling place to inhabit --- a giant A[]BnB to which we are forever “Checking In” .

*

As per your question about audience, you raise a good point – as you, Daniel, (with a similar aesthetic / philosophic / literary and cultural background) are an ideal reader, but it’s clear to me not everyone will get all the references. It was my great hope, though that there’re so many trajects, and enough “accessible” moments, that it would be able to speak to a range of audiences. The book took 4 years to write, and in that time, i tested it with a radical array of receivers readers / listeners – not only poetry crowds but those focused on Media Ecology, General Semantics, Jewish audiences, international audiences (through India, Italy, France, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Canada, UK and the US), learning how to highlight, underscore certain flavors for different occasions – ie “Fancy Bread is in thy heart and in thy head… and also at Balthazar” would be edited for whatever international bakery was most famous in that place. When reading abroad, a lot of the culturally specific references went over their head but they laughed at the Literary references. The Media Ecologists didn’t get the Poetry but loved the McLuhan, Postman, Korzybski and all that relates to television, movies and songs. The Jews love the Jewy stuff: “Salomé is listening to the Talking Heads”, “Moses is Smashing His Tablet”, “Samson is Reading the Rape of the Lock.” It’s been a kinda great learning experience.

Also, interesting you ask about having the book vs working within an arena of digital media -- as in collaboration with digital media vispo guru, Jim Andrews, we created a pretty trippy digital version of the title poem. i provided him with about 500 images that relate to the text and using dbCinema, a graphic synthesizer he developed, 'brushes' sample from these images, essentially using them as 'paint'. The images are fragmented, palimpsested, bifurcated, and in some ways highlights the construction of memory, meaning production, the materiality of language and the ever-recombinatory swirling nature of communication; how language is always-already intertextatically layered and proprioceptively received. Its seductive swathes of color texture, image typographies are synechdic of how meaning unveils itself as an ever-spiraling space where “Origin” is unlocatable; where everything is a re-articulation of a re-articulation, translation of a translation, where the past is palimpsestically re-passed, surpassed in an irrepresentable present non present or resonant present that continually escapes itself --

A still from this collab became the cover image for the book:

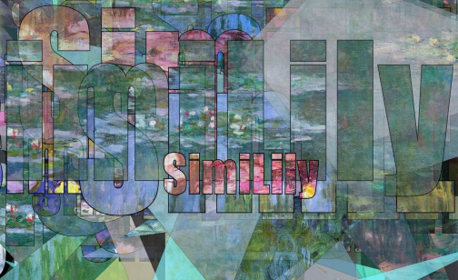

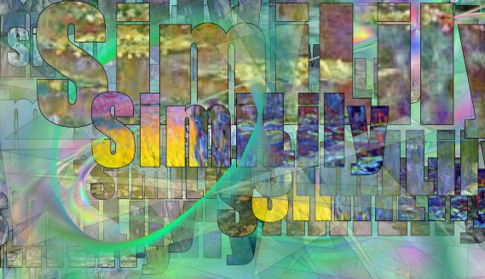

– and also the 6 page full color “Similily” in the centre of the book was created from this method as well (though in this case using 613 images of Monet’s Water Lillies).

So YES, love the digital media and these hypertextual electropoetic digitized excursions into new media --- but like the age old conundrum between orality and textuality, each medium a distinct yet confluential experience and i think (or hope) one can find pleasure through all its myriad manifestations.

Here’s the link to the full vispoetic Checking In text : )

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-syLYJ4Ma8

DM: "Checking In" is funny. You use puns and other playful language styles to draw surprising and humorous connections between and among culture makers one would not often draw together, but, which, do belong together: T.S. Eliot and the Who (teenage wasteland), Cindy Sherman and Whitman (song of selfie), Lady Macbeth and Annie (tomorrow). Can you discuss humor in your poetry? Koch, O’Hara, Ginsberg and Irving Feldman come to mind, but there isn't a ton of funny serious poetry. Is there something subversive about bringing humor (even silly humor) into an avant-garde poetics? Along these lines, irony and puns do create a relation of closeness between the joke teller (speaker) and the listener (the audience). Checking In has in its title the theme of connecting speaker to reader/listener/audience. Does your use of humor contribute to your wish to make connections with readers who must "get" the joke?

AK: I think the role of humor in poetry is such an interesting question and something that i love pushing the boundaries of --- though overtime it’s gotten me into a whack of trouble – You may remember, “I got a Crush on Osama” (2002) which was a parody of the Obama Girl video, collected in The House That Hijack Built, was featured on Fox News. In the aftermath of 9/11, everyone was literally obsessed with finding Osama bin Laden, so for me, it was a satiric intervention, “imitation with a critical difference,” (as Linda Hutcheon might say), an ironic investigation and commentary on how we are so shaped by the media apparatus, our national obsession with celebrity, how we deal with fear. At the time the video was made, the entire nation was consumed with terror, anxiety, fixated on where he was hiding. So the piece is audacious, subversive, provocative, and (in the true definition of “irony”) explodes ontologically and cuts into the fabric of things; the smooth functioning of the quiet comfortability, or the “homeyness” of our world. In so many ways, that is the role or art. And though I wasn’t thinking of it at the time, it kinda operates on the same kinda Warholian pun of “Most Wanted Men.”

This sense of disruptive comedy bleeds through much of Checking In. Perhaps, in part, one could see it as an “assimilationist” brand of Jewish humor; not of bombastic neurosis, but one that threatens to unleash chaos, creates unsocialized anarchy, embodies unpredictability. Impassioned, engaged, shticky, outrageous and earnest all at the same time – in a post Woody Allen (John Stewart / Sarah Silverman / Sandra Bernhard / Joan Rivers / Chelsea Handler) kinda way…

So much about stand up / about joke telling, really at bottom is the juxtaposition of otherness – and how that enables us to say the unsayable, elevate the mundane, mixing, combing, spinning, twisting reference, syntax, idioms --- providing different avenues of connection. And, though they often get a bad rap, in some ways, for me, punning is the highest art form, inhabiting what Freud might call a “psychic economy”, opening up the possibilities for infinite signification ; ) This sense of parodic commentary / satire has always been my preferred mode. Even as a young girl growing up in Canada, when everyone else was trading hockey cards, i collected Wacky Packages, which parody consumerism through surrealistic cartoon versions of common goods.

DM: Let me quote some things about "genre" and the rise of the construction of the canon and the idea of national literatures from Doing English: A Guide for Literature Students by Robert Eaglestone (Routledge):

"Also important for the construction of the idea of canon is the concept of genre. The poets and writers of the Renaissance (roughly 1450-1650) also produced lists, ranking the most important types, or genres, of writing ('genre' basically means 'kind' or 'type' of literary text). The British poet Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586) produced a list that classed poetry by type: epic, lyric, comic, satiric, elegaic, amatory, pastoral sonnet, epigram. Epic poetry -- about the origins of nations and peoples -- was the greatest, most enduring and most significant form, while short poems about love were the most transient and insubstantial....By the eighteenth century, it was common to find debates not only over the worth of particular genres of poetry but over the world of particular poets... The ideas of authority, authenticity, genre value and nationalism began to come together even more closely in the nineteenth century. Perhaps most influential in the formation of the canon were the many anthologies of poetry popular in the nineteenth century." (60-61)

I thought of these passages on genre, national identity, canon, and literary value as I experienced Checking In. Checking In is a genre busting text. The poem "Checking In," for example, conceptualizes a Facebook or Twitter page as a found text. "Score for Diacritics" is a concrete poem version of a musical composition score. It includes an international array of diacritical marks (umlaut; circumflex) as signs for musical notes, accompanied on the same page by a lot of white space and a line or two of doggerel verse that combines cultural theory with twisted versions of pop tunes: "let's get pataphysical" (49), a Madonna-esque punning take on Jarry's sly take on whimsical science/metaphysics. You devote four pages to a colorful art/word assemblage you co-created with Jim Andrews (“a still from the seven-minute Vispo video” [85]). In the art/text assemblage, the word "Similily" – a portmanteau that blends simile and lily and silly and simulacrum -- appears in layers of chunky but transparent fonts of various sizes filled with bits of Claude Monet's “Nympheas” water lily paintings. Your book also includes concrete poetry -- "Eros" --, poems designed by Olsonian spatial field ("In Cold Hollers"), and even a list poem made up of lines of titles for poems yet to be written. In a sense, your book is a contemporary anthology of texts that resist easy categorization. You self-consciously challenge traditional genre categorizations of what belongs (and what doesn't) in a book of "serious" poetry.

Please reflect on Checking In in terms of genre. Can you pay special attention to the connection between genre, national identification, authorial status, and the canon? You are Canadian, but you teach in New York at Pratt and travel and perform widely, so your situation challenges identification of authorial identity by nation. You are a multimedia artist/performer who does sound recordings, video poems, and whose work has appeared in many media contexts including television.

AK: For all those reasons, the notion of genre and compartmentalization has plagued me always, and as you probably know, my second book was titled “Genrecide” (1994) and features a genre busting collage essay blurring critical theory, poetry and visual elements overtly addressing the relationship between Genre and Nationalism as a kind of totalitarianistic, somewhat fascistic means discrimination saturated with outmoded ideas of Truth, Authenticity, and Closure, marked by inherent hierarchies that close down dialogue --

Perhaps it’s interesting to think about genre in some ways as Marshal McLuhan, speaks of Acoustic Space, an “inner landscape, fields of relation, elation, erration; a space which is dynamic and in flux, creating its own dimensions out of itself. This is the landscape of Checking In - not just merely mashing up “high and low discourses but an ongoing negotiation of power, definition, resistance; inscribing a language of textual hybridity and jouissance where genre explodes into an intra-subjective matrix of differential locations, allocations, r’elations displacing all sites of discrimination and domination –

And especially now whereby our “reality” is increasingly constructed (and navigated) from within our webbed networks, and our locus, a colloquy of illocatable locution recollated through screens, mirrors, phones, walls, all twittering and blogoscopic, how can we even see nation (like genre) as a thing-in-itself? Maybe better to see it as an iter[]ation; an emaNation, a dissemiNation forging (or 5G’ing itself), through 280 characters patterns; structures, codes, logics, idioms; a merger’Nation, of multiple aesthetics, styles, embodying a range of difference, errance, an invagiNation of communication strategies and procedures, of creases caverns, infolded crevices, or an enjambiNation of riffs, drifts, grifts, a calculus of constructs, foundations; an immersioNation of links, subversions excursions perversions, generating a contiguous infolding of meaning –

So yeah through all the work and especially in Checking In – there is a sense of displacement, in both form and content, highlighting how all webbed up and shticky, intratextual and hyperlinked, we can re-negotiating language, meaning, being, from continually new perspectives --

*

As you point out, my very identity en process (between Canada and America, between a variety of ethnic, political and religious identities, aesthetic communities, between genres -- as poet, performer, essayist, lecturer, media artist), there is inevitably a sense of exile, ex-staticism that bleeds through all the work; a sense of vagrancy nomadicism, that gets played out / or splayed through hyperspatial interplays. Checking In travels (travailles) through a complex of codes, texts, borders; logic systems saturated with a palimpsestic his/herstoricities, unpredictability, promiscuity, possibility, and location becomes not a specific site but an abseit cite, parasite-ations of the proper, improper, inappropriate (impropriotous, riotous), which is depropriated, exappropriated and repels, re-appelles or propels itself into place or displaced between readability and resistance; a sapirous reciprocity of paracitation, quotation, restoryation, appendices which binds a range of differences and discriminations that inform the discursive and political practices of racial and cultural hierarchization.

Heidegger says, “a boundary is not that at which something stops, but is that from which something begins its presencing”, and in a way this is the domain of Checking In, “a collection of points”, an excess of borders (or deborder, excess) – re-locating location not as a fixed, contained and stable place, but as a collusion of locution; illicit loquations, colloquations, correlations of illocatable collation, a hybrid space between ethnicities, cultures, codes; between structures of power, authority, domination; between genres, languages, dialects and ways of speaking.

And maybe, full of echoes, murmerings, it can remind us how borders themselves are always already a series of traces, echoes, cinders inscribed in a spectral economy of exile, rupture, gaps, caesuras, silences and uncertainty, and the old strongholds of genrefication have to be renegotiated.

DM: Adeena, I must ask you about your poem "Contour XLV: With Asura." It is, as Austin Powers would say, "very groovy."

I am not a Poundian, but I am familiar with Canto XLV and its anti-Semitic subtext. Myself a Jew, Pound’s screed against usury rings in my ears as I play recordings of him reading it in my classes at Purdue. So when I read your poem, I weirdly hear Pound's voice as well as your voice in duet. Instead of an anti-Semitic rant on monetary policy, however, the focus is on Asura. You offer a gloss of the obscure term: "asura:Yiddish for 'forbidden'; particularly noteworthy in Rabbi Kook's 'The Whispers of Existence'" (84).

Asura has connections with Jewish mysticism, but also Buddhist and Hindu associations with the spirit world. We can connect the term with the main character of a video game: Asura's Wrath. How do you imagine the relations between usury and Asura? Both associated with something forbidden? If we connect Asura with forbidden spirits, do you regard Pound as the daemonic ghost? Pound railed against credit, interest, borrowing money, Jews as money lenders. He was into the idea of hard currency. But, as with usury, you borrow from Pound and pay him back, with interest.

It is clever, witty, and provocative to turn Usury, the anti-Semitic trope, into Asura, a term connected with Jewish and Eastern religious mysticism, and with the "forbidden." In your version, you link the "forbidden" with the perspective, experience, and language usage of "woman."

So, the forceful, playful, and mellifluous voicings in your poem take power from a "forbidden" source -- one of Pound's most notorious anti-Semitic expressions -- that is also, in terms of poetics, a resource for contemporary avant-gardists. The avant-garde is a term of war. You use Pound, the avant-gardist extraordinaire, against himself in a battle for your own juicily excessive Écriture féminine

Is the Pound poem part of what is the "forbidden" you translate into a version of your voice? Is the "forbidden" quality of Asura related to something else we have discussed: your willingness to animate your "serious" poetry with jokes, silliness, pop referents, and punning imitations that some might view as the opposite of Highfalutin' Poundian epic modernism: the woman as "hoarder of giddy tomes" who wonders if her "cred [is] ever more than stalwart gags." And also I ask you about the focus in your Asura poem on the woman -- the Jewish woman, the erotic/ "kinky" woman of "amorous terrain," the linguistically gifted and literary-historically empowered female poet whose " COUNTER RANT" brings "pulsing to breed" while "battling the languerous grid and the bridled gloom."

AK: Daniel, Daniel, i love how through your beautifully close reading you unpack so much of what i’m doing and extend it in ways i didn’t even intend. For me, “With Asura”, is a juiced-up Jewy femme powered “Counter Rant” highlighting both Asura as forbidden and the Sanskrit Asu – whereby the “daemonic” ghost of Pound literally, figuratively, and acoustically haunts the text. But, i was not aware that Buddhist texts from ancient India define “asura” as “titan”, “demigod” or “antigod! How fabulously synchronic especially in that these “asuras…are addicted to [ ] wrath, pride, envy, insincerity, falseness, boasting, and bellicosity” and how “the state of an asura reflects the mental state of a human being obsessed with ego, force and violence”!

i too have obsessively listened to Pound’s textured reading of the original Canto, and was interested in creating a homophonic response whereby reading the two simultaneously provides a kind of trippy echography, (“with mounting treats, strong flavours / with asura the lines grow thick/ with asura [] curled re-creations…”) explodes aspects of forbiddeness. As we both know, in Hebrew, the word asura signifies that which is forbidden (referring not just to the exclusion of women, but say, the consuming of pigs or the unlawful mixing ie. milk and meat, cotton and linen), i was always also intrigued with how in Swedish, forbidden is förbJUDEN – hiding in its very name, prohibitions against Jews. Also interesting is that etymologically, from OE forbidden (from for "against" + beodan "to command", from PIE root bheudh, is to "be aware, make aware". So through the forbidding, foreboding, this sense of asura carries within it a sense of uncovering and “making aware”. (((((((t’root will set us free))))))) And also, of course --- the shift from usar to asur highlighting the non-utilitarian / consumerist aspect of art.

All to say, i was less interested in re-inscribing it with disjunctive infusions as “pure play”, but more about having it speak to that antisemetic / woman hating “bellicosity” – borrowing from the Pound text and supplanting it with all that is forbidden / policed (culturally, politically and aesthetically), underscoring the dirty practice of lending,while explosively vibrating within it, (more than) a pound of flesh ; )

Through an economy of exchange, i wanted to pay it back, pay it forward, not just with interest but also thinking about currency as in contemporary idioms, or a coeurrency all kinky and amorous yet (dis)heartened, opening a space for the ugly, the crooked, the passionate, for a fleshy um pounding. To this end, i love that you brought to my attention, one other reference for Asura, that i didn’t know, but how in Fandom, the Asura is the main protagonist of the 3D action beat 'em up game, Asura’s Wrath a powerful combatant, hot-tempered, good-hearted warrior who shows an absence of fear. In for a pound.

DM: Adeena, I found myself thinking about the theme of “leakage.” You enact “leakage” throughout your book and focus upon it in the poem “Your Leaky Day.” Please reflect on the leaky meanings/relations between image and text in your reframing of a Victorian era postcard-type sentimental style color drawing of an old fashioned of Little Bo Peep that appears in your book with the label “Ceci n’est pas une peep.”

As you can imagine, there is a lot of “deviant” art related to Little Bo Peep imagery. A good deal of it reimagines the Victorian version Little Bo Peer in ways that subvert the stereotypical version in your book. You offer the traditional image of Little Bo Peep a la Mother Goose rhyme. She is the virginal prepubescent. She is blond-curled, blue-eyed pastoral European white girl set in nature. Gazing away from the viewer, her body is concealed in an abundant array of pink skirts and petticoats and long sleeves, red vest, sun hat fastened by elaborate pink bow around neck and sturdy work boots. Her delicate right hand clutches the legendary shepherd’s crook. The crook is adorned with a blue bow and a songbird perches atop the object.

May I ask why you selected the unthreatening image of Little Bo Peep rather than one of the contemporary versions that unleash the powers, libidinal impulses, and embodied diversities suppressed in the archetypal Little Bo Peep image in your book?

Can you talk about this image as it relates to your poetics? Overall, your book plays in the space between revelation and concealment, between showing and not showing, between showing and not telling?

My question pertains to your ambivalent relation to the modernist avant-garde, a question that came up in my inquiry on Pound’s “usury” Canto as a “forbidden” aspect of your repertoire. Here, in the Little Po Peep image, you are contextualizing Mother Goose with a complex play on Magritte’s “The Treachery of Iages – This is Not a Pipe.”

Here’s the link to the full vispoetic Checking In text : )

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-syLYJ4Ma8

DM: "Checking In" is funny. You use puns and other playful language styles to draw surprising and humorous connections between and among culture makers one would not often draw together, but, which, do belong together: T.S. Eliot and the Who (teenage wasteland), Cindy Sherman and Whitman (song of selfie), Lady Macbeth and Annie (tomorrow). Can you discuss humor in your poetry? Koch, O’Hara, Ginsberg and Irving Feldman come to mind, but there isn't a ton of funny serious poetry. Is there something subversive about bringing humor (even silly humor) into an avant-garde poetics? Along these lines, irony and puns do create a relation of closeness between the joke teller (speaker) and the listener (the audience). Checking In has in its title the theme of connecting speaker to reader/listener/audience. Does your use of humor contribute to your wish to make connections with readers who must "get" the joke?

AK: I think the role of humor in poetry is such an interesting question and something that i love pushing the boundaries of --- though overtime it’s gotten me into a whack of trouble – You may remember, “I got a Crush on Osama” (2002) which was a parody of the Obama Girl video, collected in The House That Hijack Built, was featured on Fox News. In the aftermath of 9/11, everyone was literally obsessed with finding Osama bin Laden, so for me, it was a satiric intervention, “imitation with a critical difference,” (as Linda Hutcheon might say), an ironic investigation and commentary on how we are so shaped by the media apparatus, our national obsession with celebrity, how we deal with fear. At the time the video was made, the entire nation was consumed with terror, anxiety, fixated on where he was hiding. So the piece is audacious, subversive, provocative, and (in the true definition of “irony”) explodes ontologically and cuts into the fabric of things; the smooth functioning of the quiet comfortability, or the “homeyness” of our world. In so many ways, that is the role or art. And though I wasn’t thinking of it at the time, it kinda operates on the same kinda Warholian pun of “Most Wanted Men.”

This sense of disruptive comedy bleeds through much of Checking In. Perhaps, in part, one could see it as an “assimilationist” brand of Jewish humor; not of bombastic neurosis, but one that threatens to unleash chaos, creates unsocialized anarchy, embodies unpredictability. Impassioned, engaged, shticky, outrageous and earnest all at the same time – in a post Woody Allen (John Stewart / Sarah Silverman / Sandra Bernhard / Joan Rivers / Chelsea Handler) kinda way…

So much about stand up / about joke telling, really at bottom is the juxtaposition of otherness – and how that enables us to say the unsayable, elevate the mundane, mixing, combing, spinning, twisting reference, syntax, idioms --- providing different avenues of connection. And, though they often get a bad rap, in some ways, for me, punning is the highest art form, inhabiting what Freud might call a “psychic economy”, opening up the possibilities for infinite signification ; ) This sense of parodic commentary / satire has always been my preferred mode. Even as a young girl growing up in Canada, when everyone else was trading hockey cards, i collected Wacky Packages, which parody consumerism through surrealistic cartoon versions of common goods.

DM: Let me quote some things about "genre" and the rise of the construction of the canon and the idea of national literatures from Doing English: A Guide for Literature Students by Robert Eaglestone (Routledge):

"Also important for the construction of the idea of canon is the concept of genre. The poets and writers of the Renaissance (roughly 1450-1650) also produced lists, ranking the most important types, or genres, of writing ('genre' basically means 'kind' or 'type' of literary text). The British poet Sir Philip Sidney (1554-1586) produced a list that classed poetry by type: epic, lyric, comic, satiric, elegaic, amatory, pastoral sonnet, epigram. Epic poetry -- about the origins of nations and peoples -- was the greatest, most enduring and most significant form, while short poems about love were the most transient and insubstantial....By the eighteenth century, it was common to find debates not only over the worth of particular genres of poetry but over the world of particular poets... The ideas of authority, authenticity, genre value and nationalism began to come together even more closely in the nineteenth century. Perhaps most influential in the formation of the canon were the many anthologies of poetry popular in the nineteenth century." (60-61)

I thought of these passages on genre, national identity, canon, and literary value as I experienced Checking In. Checking In is a genre busting text. The poem "Checking In," for example, conceptualizes a Facebook or Twitter page as a found text. "Score for Diacritics" is a concrete poem version of a musical composition score. It includes an international array of diacritical marks (umlaut; circumflex) as signs for musical notes, accompanied on the same page by a lot of white space and a line or two of doggerel verse that combines cultural theory with twisted versions of pop tunes: "let's get pataphysical" (49), a Madonna-esque punning take on Jarry's sly take on whimsical science/metaphysics. You devote four pages to a colorful art/word assemblage you co-created with Jim Andrews (“a still from the seven-minute Vispo video” [85]). In the art/text assemblage, the word "Similily" – a portmanteau that blends simile and lily and silly and simulacrum -- appears in layers of chunky but transparent fonts of various sizes filled with bits of Claude Monet's “Nympheas” water lily paintings. Your book also includes concrete poetry -- "Eros" --, poems designed by Olsonian spatial field ("In Cold Hollers"), and even a list poem made up of lines of titles for poems yet to be written. In a sense, your book is a contemporary anthology of texts that resist easy categorization. You self-consciously challenge traditional genre categorizations of what belongs (and what doesn't) in a book of "serious" poetry.

Please reflect on Checking In in terms of genre. Can you pay special attention to the connection between genre, national identification, authorial status, and the canon? You are Canadian, but you teach in New York at Pratt and travel and perform widely, so your situation challenges identification of authorial identity by nation. You are a multimedia artist/performer who does sound recordings, video poems, and whose work has appeared in many media contexts including television.

AK: For all those reasons, the notion of genre and compartmentalization has plagued me always, and as you probably know, my second book was titled “Genrecide” (1994) and features a genre busting collage essay blurring critical theory, poetry and visual elements overtly addressing the relationship between Genre and Nationalism as a kind of totalitarianistic, somewhat fascistic means discrimination saturated with outmoded ideas of Truth, Authenticity, and Closure, marked by inherent hierarchies that close down dialogue --

Perhaps it’s interesting to think about genre in some ways as Marshal McLuhan, speaks of Acoustic Space, an “inner landscape, fields of relation, elation, erration; a space which is dynamic and in flux, creating its own dimensions out of itself. This is the landscape of Checking In - not just merely mashing up “high and low discourses but an ongoing negotiation of power, definition, resistance; inscribing a language of textual hybridity and jouissance where genre explodes into an intra-subjective matrix of differential locations, allocations, r’elations displacing all sites of discrimination and domination –

And especially now whereby our “reality” is increasingly constructed (and navigated) from within our webbed networks, and our locus, a colloquy of illocatable locution recollated through screens, mirrors, phones, walls, all twittering and blogoscopic, how can we even see nation (like genre) as a thing-in-itself? Maybe better to see it as an iter[]ation; an emaNation, a dissemiNation forging (or 5G’ing itself), through 280 characters patterns; structures, codes, logics, idioms; a merger’Nation, of multiple aesthetics, styles, embodying a range of difference, errance, an invagiNation of communication strategies and procedures, of creases caverns, infolded crevices, or an enjambiNation of riffs, drifts, grifts, a calculus of constructs, foundations; an immersioNation of links, subversions excursions perversions, generating a contiguous infolding of meaning –

So yeah through all the work and especially in Checking In – there is a sense of displacement, in both form and content, highlighting how all webbed up and shticky, intratextual and hyperlinked, we can re-negotiating language, meaning, being, from continually new perspectives --

*

As you point out, my very identity en process (between Canada and America, between a variety of ethnic, political and religious identities, aesthetic communities, between genres -- as poet, performer, essayist, lecturer, media artist), there is inevitably a sense of exile, ex-staticism that bleeds through all the work; a sense of vagrancy nomadicism, that gets played out / or splayed through hyperspatial interplays. Checking In travels (travailles) through a complex of codes, texts, borders; logic systems saturated with a palimpsestic his/herstoricities, unpredictability, promiscuity, possibility, and location becomes not a specific site but an abseit cite, parasite-ations of the proper, improper, inappropriate (impropriotous, riotous), which is depropriated, exappropriated and repels, re-appelles or propels itself into place or displaced between readability and resistance; a sapirous reciprocity of paracitation, quotation, restoryation, appendices which binds a range of differences and discriminations that inform the discursive and political practices of racial and cultural hierarchization.

Heidegger says, “a boundary is not that at which something stops, but is that from which something begins its presencing”, and in a way this is the domain of Checking In, “a collection of points”, an excess of borders (or deborder, excess) – re-locating location not as a fixed, contained and stable place, but as a collusion of locution; illicit loquations, colloquations, correlations of illocatable collation, a hybrid space between ethnicities, cultures, codes; between structures of power, authority, domination; between genres, languages, dialects and ways of speaking.

And maybe, full of echoes, murmerings, it can remind us how borders themselves are always already a series of traces, echoes, cinders inscribed in a spectral economy of exile, rupture, gaps, caesuras, silences and uncertainty, and the old strongholds of genrefication have to be renegotiated.

DM: Adeena, I must ask you about your poem "Contour XLV: With Asura." It is, as Austin Powers would say, "very groovy."

I am not a Poundian, but I am familiar with Canto XLV and its anti-Semitic subtext. Myself a Jew, Pound’s screed against usury rings in my ears as I play recordings of him reading it in my classes at Purdue. So when I read your poem, I weirdly hear Pound's voice as well as your voice in duet. Instead of an anti-Semitic rant on monetary policy, however, the focus is on Asura. You offer a gloss of the obscure term: "asura:Yiddish for 'forbidden'; particularly noteworthy in Rabbi Kook's 'The Whispers of Existence'" (84).

Asura has connections with Jewish mysticism, but also Buddhist and Hindu associations with the spirit world. We can connect the term with the main character of a video game: Asura's Wrath. How do you imagine the relations between usury and Asura? Both associated with something forbidden? If we connect Asura with forbidden spirits, do you regard Pound as the daemonic ghost? Pound railed against credit, interest, borrowing money, Jews as money lenders. He was into the idea of hard currency. But, as with usury, you borrow from Pound and pay him back, with interest.

It is clever, witty, and provocative to turn Usury, the anti-Semitic trope, into Asura, a term connected with Jewish and Eastern religious mysticism, and with the "forbidden." In your version, you link the "forbidden" with the perspective, experience, and language usage of "woman."

So, the forceful, playful, and mellifluous voicings in your poem take power from a "forbidden" source -- one of Pound's most notorious anti-Semitic expressions -- that is also, in terms of poetics, a resource for contemporary avant-gardists. The avant-garde is a term of war. You use Pound, the avant-gardist extraordinaire, against himself in a battle for your own juicily excessive Écriture féminine

Is the Pound poem part of what is the "forbidden" you translate into a version of your voice? Is the "forbidden" quality of Asura related to something else we have discussed: your willingness to animate your "serious" poetry with jokes, silliness, pop referents, and punning imitations that some might view as the opposite of Highfalutin' Poundian epic modernism: the woman as "hoarder of giddy tomes" who wonders if her "cred [is] ever more than stalwart gags." And also I ask you about the focus in your Asura poem on the woman -- the Jewish woman, the erotic/ "kinky" woman of "amorous terrain," the linguistically gifted and literary-historically empowered female poet whose " COUNTER RANT" brings "pulsing to breed" while "battling the languerous grid and the bridled gloom."

AK: Daniel, Daniel, i love how through your beautifully close reading you unpack so much of what i’m doing and extend it in ways i didn’t even intend. For me, “With Asura”, is a juiced-up Jewy femme powered “Counter Rant” highlighting both Asura as forbidden and the Sanskrit Asu – whereby the “daemonic” ghost of Pound literally, figuratively, and acoustically haunts the text. But, i was not aware that Buddhist texts from ancient India define “asura” as “titan”, “demigod” or “antigod! How fabulously synchronic especially in that these “asuras…are addicted to [ ] wrath, pride, envy, insincerity, falseness, boasting, and bellicosity” and how “the state of an asura reflects the mental state of a human being obsessed with ego, force and violence”!

i too have obsessively listened to Pound’s textured reading of the original Canto, and was interested in creating a homophonic response whereby reading the two simultaneously provides a kind of trippy echography, (“with mounting treats, strong flavours / with asura the lines grow thick/ with asura [] curled re-creations…”) explodes aspects of forbiddeness. As we both know, in Hebrew, the word asura signifies that which is forbidden (referring not just to the exclusion of women, but say, the consuming of pigs or the unlawful mixing ie. milk and meat, cotton and linen), i was always also intrigued with how in Swedish, forbidden is förbJUDEN – hiding in its very name, prohibitions against Jews. Also interesting is that etymologically, from OE forbidden (from for "against" + beodan "to command", from PIE root bheudh, is to "be aware, make aware". So through the forbidding, foreboding, this sense of asura carries within it a sense of uncovering and “making aware”. (((((((t’root will set us free))))))) And also, of course --- the shift from usar to asur highlighting the non-utilitarian / consumerist aspect of art.

All to say, i was less interested in re-inscribing it with disjunctive infusions as “pure play”, but more about having it speak to that antisemetic / woman hating “bellicosity” – borrowing from the Pound text and supplanting it with all that is forbidden / policed (culturally, politically and aesthetically), underscoring the dirty practice of lending,while explosively vibrating within it, (more than) a pound of flesh ; )

Through an economy of exchange, i wanted to pay it back, pay it forward, not just with interest but also thinking about currency as in contemporary idioms, or a coeurrency all kinky and amorous yet (dis)heartened, opening a space for the ugly, the crooked, the passionate, for a fleshy um pounding. To this end, i love that you brought to my attention, one other reference for Asura, that i didn’t know, but how in Fandom, the Asura is the main protagonist of the 3D action beat 'em up game, Asura’s Wrath a powerful combatant, hot-tempered, good-hearted warrior who shows an absence of fear. In for a pound.

DM: Adeena, I found myself thinking about the theme of “leakage.” You enact “leakage” throughout your book and focus upon it in the poem “Your Leaky Day.” Please reflect on the leaky meanings/relations between image and text in your reframing of a Victorian era postcard-type sentimental style color drawing of an old fashioned of Little Bo Peep that appears in your book with the label “Ceci n’est pas une peep.”

As you can imagine, there is a lot of “deviant” art related to Little Bo Peep imagery. A good deal of it reimagines the Victorian version Little Bo Peer in ways that subvert the stereotypical version in your book. You offer the traditional image of Little Bo Peep a la Mother Goose rhyme. She is the virginal prepubescent. She is blond-curled, blue-eyed pastoral European white girl set in nature. Gazing away from the viewer, her body is concealed in an abundant array of pink skirts and petticoats and long sleeves, red vest, sun hat fastened by elaborate pink bow around neck and sturdy work boots. Her delicate right hand clutches the legendary shepherd’s crook. The crook is adorned with a blue bow and a songbird perches atop the object.

May I ask why you selected the unthreatening image of Little Bo Peep rather than one of the contemporary versions that unleash the powers, libidinal impulses, and embodied diversities suppressed in the archetypal Little Bo Peep image in your book?

Can you talk about this image as it relates to your poetics? Overall, your book plays in the space between revelation and concealment, between showing and not showing, between showing and not telling?

My question pertains to your ambivalent relation to the modernist avant-garde, a question that came up in my inquiry on Pound’s “usury” Canto as a “forbidden” aspect of your repertoire. Here, in the Little Po Peep image, you are contextualizing Mother Goose with a complex play on Magritte’s “The Treachery of Iages – This is Not a Pipe.”

Your image text of Little Bo Peep/“Ceci n’est pas une peep” literally and figuratively faces in a dual-page format your poem called “Lov3r’s Squall.” This poem is a mock up, according to your helpful notes, of Khalil Gibran’s “A Lover’s Call XXVII.” (I should say that your book is quite a network of textuality; I’ve done a lot of googling to try to keep up with your referentiality!). By placing the NOT Little Bo Peep in dual face with your revision of Gibran’s “A Lover’s Call,” you literally make NOT Little Bo Peep appear to be uttering your version of “A Lover’s Call.” Your NOT Little Bo Peep, in other words, is not in search of wandering sheep, but rather, in search of “my beloved” (Gibran). And yet, in your version of “A Lover’s Call,” the desire for the beloved is cast in terms of the desire to find one’s own voice in song: “Where are you, my bevelled aria? (57). Your image of Not Little Bo Peep motivated me to read the Mother Goose poem “Little Bo Peep.” The version of the poem that appears on the Poetry magazine website is quite stunning in its surreal weirdness and Freudian potentialities. The Mother Goose poem alludes to dream, desire, loss, mourning, and even castration and death when Bo Peep awakens to find: “their tails, side by side, / All hung on a tree to dry.” Your work certainly encourages a form of active reading/reception of intertexts, both within and among your texts, and also in relation to your sources texts: Mother Goose, Magritte, Gibran, and the “deviant” versions of Bo Peep that I found via Google images.

AK: omg Daniel your exegesis, your attention is startlingly astute, observant – again all the ways i consciously intended and so many others that i wasn’t even aware of in the writing. With “Ceci n’est pas une peep” i was motivated predominantly by the pun of it – and opted for the most, albeit clichéd image to pair it with, because like a cliché itself, i love the idea of taking some old worn out phrase, revitalizing, recycling it; hijacking it and dyssemically thrusting it into new socio-linguistic zones. And i was totally attracted to the simple ridiculousness of juxtaposing the “stereotypical” Mother Goose image with the Magritte, sifting it through a kinda ‘pataphysical historicity and having each cultural referent “leak” into the other – which for me felt “deviant” all on its own.

It is so exciting though to be made aware of these other transgressive bo peep images – which i had no knowledge of. Particularly thrilling is this one:

AK: omg Daniel your exegesis, your attention is startlingly astute, observant – again all the ways i consciously intended and so many others that i wasn’t even aware of in the writing. With “Ceci n’est pas une peep” i was motivated predominantly by the pun of it – and opted for the most, albeit clichéd image to pair it with, because like a cliché itself, i love the idea of taking some old worn out phrase, revitalizing, recycling it; hijacking it and dyssemically thrusting it into new socio-linguistic zones. And i was totally attracted to the simple ridiculousness of juxtaposing the “stereotypical” Mother Goose image with the Magritte, sifting it through a kinda ‘pataphysical historicity and having each cultural referent “leak” into the other – which for me felt “deviant” all on its own.

It is so exciting though to be made aware of these other transgressive bo peep images – which i had no knowledge of. Particularly thrilling is this one:

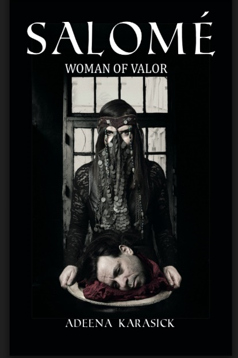

as while writing Checking In, i was firmly enmeshed in the Salomé: Woman of Valor project – (my spoken word opera, with composer, Frank London), revisioning the apocryphal figure through a Jewish Feminist lens and liberating her from the anti-semitic, somewhat misogynist Oscar Wilde text and back into her rightful place in history as a powerful, Jewish matriarch. So, this image you found of bo peep literally beheading the sheep is so beautifully synchronous with the beheading of John the Baptist –

And in both images, the decapitated head needn’t be seen as a trophy per se, but a site of multiplicity, dialogy. Separated, the head foregrounds the thinking body, a site of the absent present, of lost referents, of apostrophic spectrality. Or thought through a Kabbalistic lens, the separation of the head from the body pays homage to the separation of the primordial letters. Heady!!

In any case, when constructing “Ceci n’est pas une peep”, (maybe because of my working on Salomé and consumed with how she was scapegoated throughout history), i was thinking about sheep in relation to goats and how, as you know according to Jewish tradition in Temple times, the Priest would put all the sins of the people onto the goat and send it into the forest or sacrifice it. So, was thinking about poor bo peep and wondering how in fact DID she lose her sheep??? How they were maybe “on the lam” ; ) In the words of Christopher Smart, i was totally “Rejoicing in the Lam[], the Lamb from bedlam, or as Blake says in Little Lamb, “giving clothing of delight…making all the v[eil]s rejoice!” she, sheepishly, says --

Also, it’s interesting that you highlight the fact that the bo peep image i use in Checking In is one of the “the virginal prepubescent” – because that is exactly what Salomé has been historically represented as. And in both cases, i am recontextualizing these virginal girls, imbuing them with something “other,” a kind of weightier history.

And in Checking In, yes, she is yes, my bo is indeed peeping with her gaze not toward her wandering sheep but, toward the homophonic tran’elated Gibran -- because for me she is calling out and into all that is wandering as in diferrance, all that cannot be contained, all that is inscribed with difference, desire, highlighting how all of language and meaning production is a process of veiling and unveiling, of avails, values, volés; of clarity and obfuscation, how nothing is what it is, (ceci n’est pas une [ ]), as i lay “their ta[le]s, side by side, / hung [as treats] to [t]ry.”

In any case, when constructing “Ceci n’est pas une peep”, (maybe because of my working on Salomé and consumed with how she was scapegoated throughout history), i was thinking about sheep in relation to goats and how, as you know according to Jewish tradition in Temple times, the Priest would put all the sins of the people onto the goat and send it into the forest or sacrifice it. So, was thinking about poor bo peep and wondering how in fact DID she lose her sheep??? How they were maybe “on the lam” ; ) In the words of Christopher Smart, i was totally “Rejoicing in the Lam[], the Lamb from bedlam, or as Blake says in Little Lamb, “giving clothing of delight…making all the v[eil]s rejoice!” she, sheepishly, says --

Also, it’s interesting that you highlight the fact that the bo peep image i use in Checking In is one of the “the virginal prepubescent” – because that is exactly what Salomé has been historically represented as. And in both cases, i am recontextualizing these virginal girls, imbuing them with something “other,” a kind of weightier history.

And in Checking In, yes, she is yes, my bo is indeed peeping with her gaze not toward her wandering sheep but, toward the homophonic tran’elated Gibran -- because for me she is calling out and into all that is wandering as in diferrance, all that cannot be contained, all that is inscribed with difference, desire, highlighting how all of language and meaning production is a process of veiling and unveiling, of avails, values, volés; of clarity and obfuscation, how nothing is what it is, (ceci n’est pas une [ ]), as i lay “their ta[le]s, side by side, / hung [as treats] to [t]ry.”